What was The Broadcasting Museum?

Broadcasting was one of the most significant factors in

the development of 20th century culture. For the first time, one person

could address a nation simultaneously in their own homes. News, music and

entertainment could be made available to all who wanted it. A single

teacher could teach a million people, a single musician could play before

an audience that would have been undreamed of in the previous

century.

The technology of radio and television has changed

enormously over a relatively short time, and artefacts from even the

recent past have become outdated so fast that they have all but

disappeared. The Broadcasting Museum was set up in 1994 to tell the story

of these once-familiar objects in the context of the rapidly changing

twentieth century. It was a private collection, and the museum, which was

part of On The Air, relied solely on admission charges. It attracted a

lot of acclaim, and was seen by thousands of visitors from all over

the world.

However, due to the expiry of the lease on the premises in

Chester, the Museum closed at the end of September 2000. The collection was not dispersed, as it was bought by the

BBC - hopefully to form the nucleus of a national exhibition of British Broadcasting, although to date this has not yet happened.

You have missed the chance to visit the Museum in it's

original setting, but you can take a virtual tour right now without

leaving your seat.

The Birth of

Radio

As you entered the

Museum, the displays started with the beginning of radio, or wire-less

telegraphy, as it was first called. Before wireless, the only means of

long range communication was the telephone, and you could use a telephone

exchange of the type in use from the 1920s to listen to Guiglielmo Marconi

explain how he came to Britain in the 1890s to further his

experiments.

Marconi's discoveries

led to the use of wireless as a means of Morse code communication with

shipping, and later on it was discovered that voice and even music could be

sent. The possibilities of this as a public service were realised by the

main manufacturers of wireless equipment, who set up the British

Broadcasting Company in 1922.

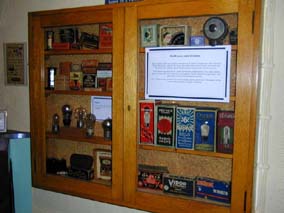

Examples of wireless

sets from the 1920s are shown in the display case. At first, wireless was

more of a hobby than an entertainment or information medium.

Some 1920s radios from the archives of On The Air

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AJS Type 'F' |

Marconi V1 |

Marconi Crystal Junior RB2 |

Graves 'Vulcan' |

Gecophone No.2 Crystal set |

BTH Radiola 2 |

The simplest receiver

was a crystal set, which used a mineral crystal (usually Galena) as a

rectifier, and enabled the listener to tune in the station on headphones,

assuming they were within range of a station, had a 100 foot long aerial,

and could locate a sensitive part of the crystal using a wire probe called

a "cat's whisker".

To obtain greater

range or volume, a valve receiver was needed. This was much more expensive

- a valve could cost a week's wages and was easily damaged. Valve radios

required electricity from batteries, a large High Tension battery giving

about 120 volts, and a Low Tension accumulator, which could be recharged

like a modern mobile phone or laptop battery. The difference was, it

weighed several pounds and could spill corrosive acid. Most radio owners

had two, one to use and one being charged. Cycle shops and garages, as

well as wireless dealers would recharge accumulators for about

6d.

One person could

listen on headphones, but for a family to 'listen in' a loud-speaker was

needed. These at first were metal or wooden horns fixed to a telephone

receiver. Visitors could compare the sound of an early Horn speaker with the

later Moving Iron cone speaker, and the Moving Coil type, which appeared

just before 1930. This is the type we still use today.

Many enthusiasts

built their own sets. There were examples of these in the Museum, and of the components

that could be bought for home construction.

Radio became the

latest craze, and was the subject of numerous magazines, postcards, and

even puzzles. Examples of these, and the range of parts available for home

construction were on display in this area.

Through the window

you could see into a 1920s living room, with a young lady trying to hear the

latest dance music on the new wireless set, complete with batteries,

accumulator and a huge frame aerial.

How Radio

Works

If you wanted to know

more about how radio actually works, and see how your voice is turned into

a radio signal, there was a display where you could find out for yourself.

Visitors could speak

into the microphone and see their voice turned into an electrical signal,

shown on an oscilloscope. The display then showed the same signal as it is

modulated on the carrier wave, the high-frequency radio signal that

carries the sound (lower) frequencies through the air from the transmitter to the

receiver.

On pressing a button,

the signal is demodulated, cutting off the carrier and restoring the sound

signal. This is what happens in an Amplitude Modulated (A.M.) type of radio set.

The

North Regional BBC Transmitter

Also in this area were

some parts from one of the first BBC regional transmitters, Moorside Edge,

which broadcast the North Regional programme from the high moors near

Huddersfield. It was opened in 1931, and the transmitter building was an

impressive piece of industrial architecture.

The huge copper coil

and the meters mounted on a slate panel were part of the state of the art

high power transmitter, shown in a contemporary Exide battery

advertisement above the exhibit. The transmitter was built by the Marconi

company, and opened in 1931. It was only taken out of service in the

1980s.

The Exide batteries

advert came from a radio shop in Newport, South Wales. It had been on the

wall in the workshop for at least 60 years.

The shop, Lloyd &

Lloyd, was typical of many that diversified into wireless in the 1920s. It

was an ironmongers shop, that sold everything from paraffin to

agricultural implements, but when the proprietor became interested in

wireless, he began to sell sets and parts. They then began to build their

own sets for sale, examples of which have been seen.

Later on, they became

agents for major manufacturers. The son of the founder said that he

remembered his father setting up a horn loudspeaker outside the shop so

that passers-by could hear the latest news of the General Strike in 1926.

The carbon filament bulb in the Wartime area of the museum was from the

unsold stock in the shop, and is at least 50 years old. It was

working every day for several years, and already outlasted many modern

bulbs.

The Golden Age of

Radio

By 1930 the wireless

set was no longer an experimental apparatus, nor the enthusiast's toy. It

was a practical means of home entertainment, providing news, music and

education.

It moved from the

'Wireless Den' into the living room or parlour, and had now to look like a

piece of furniture. Manufacturers wanted their sets to appear simple to

operate, so out went complicated panels cluttered with knobs and switches,

while in came the new motifs of the Jazz Age - Art Deco inspired geometric

shapes, fretwork inspired by leaves or sunsets, and new, innovative shapes

that had their origins in the Art Schools of Europe.

Wireless cabinets had

to appeal for the first time to the lady of the house, who often had the

decisive vote in the choice of set. Manufacturers realised that the

appearance of the set was every bit as important in making a sale as the

technical prowess. The more affordable sets were becoming more and more

standardised technically anyway.

One of the most aesthetically

different designs for a radio cabinet was produced for Ekco Radio Ltd by

architect and designer Wells Coates, who amongst other projects designed

part of BBC Broadcasting House, which opened in 1932. This radio set was

of a circular shape, and unlike any other cabinet produced at that time.

It was moulded in a new material, Bakelite, which was cheaper than the

veneered wood used for most cabinets. Ekco had pioneered the use of this

material in Britain since 1930, but the circular model AD65 is now

considered a classic, as it was the first Bakelite cabinet to exploit the

moulding potential of the material, rather than imitating

wood.

Many other

manufacturers produced interesting and unusual designs, as demand

increased and almost every household aspired to own a wireless set. Most

people could still not afford to buy a set outright, but instead opted to

buy on Hire Purchase. Retailers and manufacturers offered their own

schemes, but as prices fell throughout the 1930s, competition was

strong.

One of the cheapest

sets on offer was the Philco "People's Set", available from 6 Guineas

(£6.6s). This was a British made set by an American manufacturer,

available in various forms to suit the different range of mains

electricity across the country. Some areas had AC, some DC, and at

voltages from 200 to 250. Many rural areas had no electricity, so the

battery model was still a popular choice.

Some 1930s radios from the archives of On The Air

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ekco SH25 |

Marconi 264 |

Philco 'Empire Automatic' |

Ekco AC97 |

Philips 'Radioplayer' |

Bush AC3 |

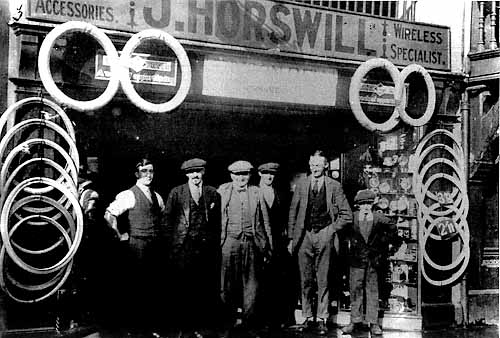

Wireless was the boom industry of the 1930s, and every

town had shops selling and repairing wireless sets. Some were extensions

of existing businesses, often cycle shops or even ironmongers. The site of

the Museum was such a shop - originally Horswill's Cycles, it later

specialised in wireless. This photograph was taken around 1930, and the

business still existed in Northgate Street, Chester, at the time the Museum was open.

When the Museum was being set up, we

did not know the history of the shop, so we invented our own shop,

'Nixon's', taken from an old illuminated sign that was used outside the

window. All the signs, posters and items used inside the shop are

original, but the fabric of the shop is of course fake, done by the scenic

artists who created the studio sets for many well known programmes,

including 'Coronation Street'.

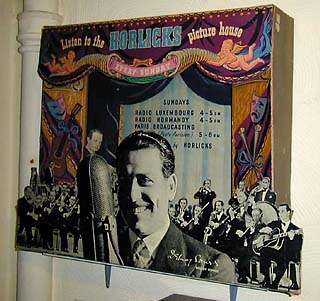

The BBC was the

only organisation allowed to broadcast in Britain. They were forbidden

from carrying any form of advertising, but some businesses wanted

commercial radio to be available. Radio stations were set up in France and

Luxembourg with their transmissions beamed into Britain, and they

broadcast on a Sunday, when light music was not broadcast by the BBC.

This advertisement display is for the Horlicks radio shows

on Radio Luxembourg and Radio Normandie, where popular dance bands like

Debroy Somers played to an audience based mainly in the South of England.

Television Begins

Television was only experimental until 1936, the BBC having tested transmissions of John Logie Baird's 30 line mechanical disc system from 1929, but it was abandoned in 1935 when it was realised that it was never going to be able to provide a viable service. Baird himself now had an improved 240 line system, but the fully electronic system developed by Marconi-EMI using 405 lines was a far superior method. The BBC set up studios and transmitters to test both systems at Alexandra Palace, but the Baird system was discontinued in 1937.

From 1936 until the TV service closed down in 1939 the service was only available to viewers within about 50 miles of London. There would have been little chance of receiving a TV picture in the North-West of England, so it is unlikely that there were any TV sets at all in this area until 1946.

Pre-war Television sets from the archive of On The Air

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Baird Televisor |

Televisor Kit |

RGD 382RG TV/Radiogram (1938) |

Marconi model 706 TV/Radio(1938) |

Pye 815 (1939) |

Cossor 900 (Immediate post war re-issue of 1939 model) |

Wireless at

War

With the outbreak of war in September 1939, the

manufacture of domestic radios was virtually stopped, as factories turned

to making radio and radar equipment for the armed services.

Many of the qualified service engineers were called up ,

and local shops were unable to repair sets for customers, due to shortages

of staff and parts. Valves became scarce, and certain types were only

obtainable with a government permit, as it was suggested that they could

be used to make transmitters for espionage.

The Television Service, at the time only available in the

London area, was closed down immediately, as the VHF signal would provide

a beacon for enemy bombers. The National station at Droitwich was closed

for the same reason, and all regional transmitters now radiated the same

programme to make identification more difficult.

The New communications equipment was put into production

for the land, sea and air forces.

The Museum collection included the Murphy B40 receiver for

the Navy, the Wireless Set No 18 manpack for the Army, and two examples of

RAF airborne transmitter/ receivers, the TR9 and T1154/R1155 combinations

as used by Bomber Command. The R1155 was operational, and visitors could tune

in to today's news on this famous wartime receiver.

There were also examples of the German People's Set, the

'Deutche Kleinempfanger', the MCR1 miniature communications receiver,

which was dropped into occupied territory.

The shortage of

new receivers was a problem, as the government wanted the population to be

able to hear news bulletins and entertainment programmes from the BBC. A

cheap receiver was designed and produced under government direction,

called the Wartime Civilian Receiver, made by any manufacturer with

available parts to a standard design. They were Medium Wave only, marked

with 'Home' and 'Forces' programmes only on the scale.

This section of the museum was constructed like an air raid

shelter, with wartime artefacts that would have been found there. In the

display case are wartime advertisements and news cuttings, as well as

radios from the period.

Post-War British

Radio and Television

The Ekco A22, Murphy A104, Bush DAC90

were all shown at the "Britain Can Make It" exhibition.

After the war, radio and now television were fast becoming the main source of news and entertainment.

When the war was over, British industry was in need of

regeneration. Attention was fixed on exports, and with experience gained

on war work, technology was seen as an important area. An exhibition was staged in 1946, called "Britain Can Make

It", to show the world that British industry was back in business. The

radio manufacturers were keen to show new models that would gain export

contracts. Bush, Ekco and Murphy all had new models that set new

standards in design and reliability.

Some post-war radios from the archives of On The Air

The Television Service resumed transmissions from London

in 1946, and plans were immediately put into operation for a nation-wide

service, although some areas were not covered until well into the 1950s.

Displays in this section covered the growth of television in

the 1950s, alongside the reduction in size of radio sets due to the

development of miniature components. 1950s catalogues and advertisements,

mainly for radios and TVs, but also for cars and clothes set the

scene. The TV sets shown date from about 1949 onwards, and the

Vidicon tube TV camera, which is ex-BBC, dates from the late

1950s. Examples of 1950s TV station idents and 1950s programmes

could be seen on the bakelite Bush TV22, or the picture from the TV studio

set opposite.

A set of a 1950s living room, complete with radiogram and slimline TV set. This was constructed as a 'set' in a TV studio, with cameras and sound boom. The radiogram was a Pye model incorporating the 'Record maker' device which was a magnetic disc, similar in operating principle to the modern hard disc. It was meant for home recording but never caught on. The cameras are by Link and Marconi.

Some post-war television sets from the archives of On The Air

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Baird Townsman |

Pye V4 |

Mullard MTS389 |

Bush TV43 |

HMV 1801 |

Bush TV22 |

Television

Technology

The basic concept of the cathode ray receiver has not

altered much since the system was introduced in 1936.

The main improvements in picture definition and later in colour

transmission were due to developments in the camera technology.

The earliest camera in the collection is a Pye MK3 Image

Orthicon camera dating from 1955. Early (c.1967) colour cameras by EMI and

Marconi were also on display, along with later versions that gradually show

the reduction in size that has been achieved. The most recent was a Sharp

Viewcam, a domestic camcorder that contains all the elements of the early

cameras, and a video tape recorder in a single unit that can be held in

one hand. This was the best home technology then available, kindly loaned by Sharp UK in 1995.

The changes in

radio and television design in the last thirty years have mainly been

achievable because of miniaturisation. Examples of transistor radios from

the 1960s onwards and pocket TVs were on display along with some reminders

of the times, such as the 'Pop Pirates and the launch of Radio

1.

The method by which light is converted into an electrical

signal, and the signal is converted back into a picture using a cathode

ray tube was illustrated in the Museum by an interactive video. The picture

signal from the video, as well as appearing on a screen, appeared in

graphic form on a waveform monitor, which allowed the visitor to see one

line of the picture displayed as an electrical signal.

The last section of the museum was a reconstruction of a TV

studio control gallery, with sound and vision mixing consoles, monitors

and studio quality audio tape recorders.

The audio mixer originally came from a BBC outside

broadcast unit, and the vision mixer from ITN.

Television Technology- a continuing collection

Although the musem was closed in 2000, and the collection passed to the BBC, we have continued to collect items of television technology, especially cameras and VTRs. Have a look at our collection HERE or click the camera image.

|

Dial 'M' for Marconi! The story of Marconi's first experiments, told by an actor playing the famous Italian inventor.

1920s display cabinet, showing crystal sets, valve radios and period memorabilia. Visitors could listen to different types of loud-speaker playing 1920s radio programmes.

19203/30s valves and components. Many people built their own sets.

The 1920s room display. The model is wearing an authentic 'Flapper' dress, and is listening-in on an Edison Bell wireless, with batteries and a 'frame aerial'. This would have been used by flat-dwellers or others who could not put up the 100ft long outside wire which was usually a feature.

Humerous postcards with radio themes.

Looking into the window of the 1920s room.

How Radio Works. Visitors could see their own voice modulated onto a carrier wave, and see how the signal is 'detected'.

Wireless sets of the 1930s. The set was becoming a piece of furniture.

A classic design, by architect Wells Coates for E' K' Cole Ltd. the model AD65 of 1934.

An advert for a popular radio, the Philco 'People's Set. 1936.

The recreation of a 1930s wireless shop in the museum. The name was derived from an illuminated sign. The shop contained many items you would have found in a typical small radio shop at the time.

Wireless goes to war. This section showed how the radio industry was mobilised to help with the war effort. the set shown was an Army Wireless Set No. 17, used for Ack-Ack gun communications.

The wartime civilian receiver. Made under Government direction by all radio manufacturers to ensure people would have radios to listen to important news, especially in the event of invasion.

All the armed services needed radio, examples shown are the Murphy B40 Naval receiver, the R1155 and T1154 sets used in Bomber Command planes, and the TR9 set used in the Spitfire and Hurricane fighters.

A display of wartime memorabilia and radio related items. The setting is an air-raid shelter, with bunk beds, an ARP helmet and gas masks to hand.

|